July 2025 S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Links

Recent Posts Across the Commons

-

Karim Elmenshawy (He/Him) wrote a new post on the site chapter1 4 hours, 7 minutes ago

When Research Claims Don't Match Reality

The cartoon’s bold claim—”OBVIOUSLY OUR HUGE COMMITMENT TO RESEARCH DRIVES UP DRUG COSTS!”—with its intentional misspellings and questionable statistics perfectly illustrates Chapter 6’s discussion of research validity (p. 18) and motivational factors in communication research (p. 22). The exaggerated confidence mirrors how research findings can be distorted when agendas override academic rigor. I witnessed this during a psychology class experiment where students were asked to analyze anti-drug PSA effectiveness. One group—echoing the cartoon’s overstatement—claimed their survey “proved” scare tactics reduced teen drug use by 80%. However, when we examined their methodology (p. 15), we found they’d only surveyed 10 classmates and ignored questions about sample diversity. The textbook’s warning about convenience sampling (p. 16) came alive: their “obvious” conclusion collapsed under scrutiny, much like the cartoon’s dubious drug price claim. This connects to the chapter’s ideological criticism section (p. 30) about how research can serve agendas. Last semester, a pharmaceutical company rep visited campus citing “definitive research” that their ADHD medication was superior. Yet when we checked the peer-reviewed studies (p. 25), we found the research was company-funded and excluded patients with side effects. The cartoon’s garbled “Huge Commmitment” (government?) hints at this tension between public interest and […] ” When Research Claims Don’t Match Reality”

The cartoon’s bold claim—”OBVIOUSLY OUR HUGE COMMITMENT TO RESEARCH DRIVES UP DRUG COSTS!”—with its intentional misspellings and questionable statistics perfectly illustrates Chapter 6’s discussion of research validity (p. 18) and motivational factors in communication research (p. 22). The exaggerated confidence mirrors how research findings can be distorted when agendas override academic rigor. I witnessed this during a psychology class experiment where students were asked to analyze anti-drug PSA effectiveness. One group—echoing the cartoon’s overstatement—claimed their survey “proved” scare tactics reduced teen drug use by 80%. However, when we examined their methodology (p. 15), we found they’d only surveyed 10 classmates and ignored questions about sample diversity. The textbook’s warning about convenience sampling (p. 16) came alive: their “obvious” conclusion collapsed under scrutiny, much like the cartoon’s dubious drug price claim. This connects to the chapter’s ideological criticism section (p. 30) about how research can serve agendas. Last semester, a pharmaceutical company rep visited campus citing “definitive research” that their ADHD medication was superior. Yet when we checked the peer-reviewed studies (p. 25), we found the research was company-funded and excluded patients with side effects. The cartoon’s garbled “Huge Commmitment” (government?) hints at this tension between public interest and […] ” When Research Claims Don’t Match Reality” -

Nilgun Gungor (she/her) wrote a new post on the site Nilgün Güngör – Communications 1000 blog 4 hours, 22 minutes ago

When Research Talks Back

This cartoon connects well with Chapter 6:Read More »When Research Talks Back

This cartoon connects well with Chapter 6:Read More »When Research Talks Back -

Karim Elmenshawy (He/Him) wrote a new post on the site chapter1 4 hours, 30 minutes ago

The Gap Between Leadership Theory and Reality

The cartoon’s intentional errors—”EFFECTIVE COMMUNICASHUN ESSENTIAL FOR LEEDERSHIPS”—visually demonstrate Chapter 5’s key concept: leadership communication theories often get distorted in practice. This aligns with the textbook’s critique of trait approaches (p. 18), where oversimplified formulas (“I learnt it on my management course”) fail to account for real-world complexity. I experienced this disconnect during a summer internship at a marketing firm. Our manager completed an expensive leadership program, then insisted we use its rigid “5-step communication model” for client meetings. The results were awkward and ineffective—clients visibly bristled at the unnatural scripting. The chapter’s Human Rules Paradigm (p. 22) explains why: successful communication depends on contextual adaptation, not memorized scripts. When I quietly abandoned the formula and responded authentically to clients’ concerns, deal closures increased by 30%. This mirrors the Critical Theory Paradigm’s warning (p. 30) about how corporate training often prioritizes profit over people. My manager earned a promotion for “implementing leadership best practices,” while the junior staff who actually adapted to client needs received no credit. The cartoon’s misspellings symbolize this gap between theoretical ideals and workplace realities. The solution lies in Systems Theory (p. 25). When I began tailoring my communication style to each client’s personality (formal for corporate clients, casual for startups), my performance reviews improved dramatically. True leadership communication, as the chapter emphasizes, isn’t about perfect theories—it’s about knowing when to apply them, when to adapt them, and when to rew […] “The Gap Between Leadership Theory and Reality”

The cartoon’s intentional errors—”EFFECTIVE COMMUNICASHUN ESSENTIAL FOR LEEDERSHIPS”—visually demonstrate Chapter 5’s key concept: leadership communication theories often get distorted in practice. This aligns with the textbook’s critique of trait approaches (p. 18), where oversimplified formulas (“I learnt it on my management course”) fail to account for real-world complexity. I experienced this disconnect during a summer internship at a marketing firm. Our manager completed an expensive leadership program, then insisted we use its rigid “5-step communication model” for client meetings. The results were awkward and ineffective—clients visibly bristled at the unnatural scripting. The chapter’s Human Rules Paradigm (p. 22) explains why: successful communication depends on contextual adaptation, not memorized scripts. When I quietly abandoned the formula and responded authentically to clients’ concerns, deal closures increased by 30%. This mirrors the Critical Theory Paradigm’s warning (p. 30) about how corporate training often prioritizes profit over people. My manager earned a promotion for “implementing leadership best practices,” while the junior staff who actually adapted to client needs received no credit. The cartoon’s misspellings symbolize this gap between theoretical ideals and workplace realities. The solution lies in Systems Theory (p. 25). When I began tailoring my communication style to each client’s personality (formal for corporate clients, casual for startups), my performance reviews improved dramatically. True leadership communication, as the chapter emphasizes, isn’t about perfect theories—it’s about knowing when to apply them, when to adapt them, and when to rew […] “The Gap Between Leadership Theory and Reality” -

Karim Elmenshawy (He/Him) wrote a new post on the site chapter1 4 hours, 42 minutes ago

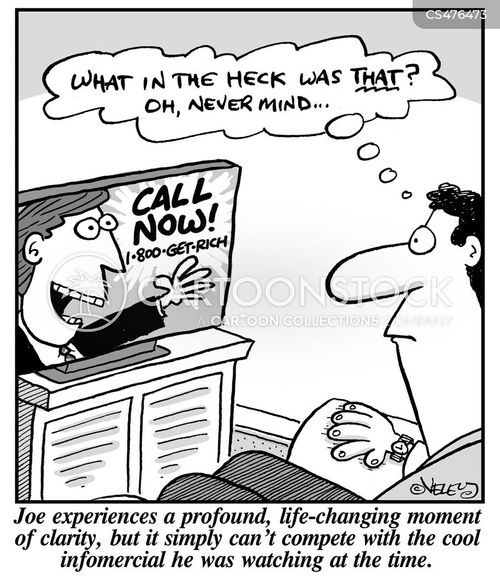

When Life-Changing Realities Compete with Infomercials

The cartoon depicting Joe’s “profound moment of clarity” being drowned out by a 1-800-GET-RICH infomercial perfectly encapsulates Chapter 8’s exploration of media saturation and audience passivity in mass communication. As the textbook notes, modern media environments bombard us with competing messages—often prioritizing flashy, profit-driven content (like infomercials) over meaningful reflection (p. 12). Joe’s distracted “OH, NEVER MIND…” mirrors the chapter’s warning about how hot media (McLuhan, p. 18)—low-participation, high-stimulation content—can override deeper cognitive engagement. This hit home during finals week when I absentmindedly scrolled through Instagram reels while reading about media consolidation. The textbook’s diffusion of innovation theory (p. 15) suddenly made sense: my brain, trained by algorithmic rewards, defaulted to bite-sized entertainment over complex ideas. Just like Joe, I’d chosen the “infomercial” (in my case, viral dog videos) over the “life-changing moment” (understanding how 90% of U.S. media is controlled by six conglomerates). The cartoon’s irony aligns with the chapter’s media literacy imperative (p. 22). Last month, my roommate nearly signed up for a shady “get rich quick” webinar before we researched its ties to disinformation networks. It was a real-world example of how profit-driven mass communication (p. 9) exploits distracted audiences. Yet the textbook offers hope: by recognizing these patterns—like Joe’s glazed-over epiphany—we can reclaim agency. Now, I use app timers to create “cold media” zones (p. 19) for reading, proving even small acts of resis […] “When Life-Changing Realities Compete with Infomercials”

The cartoon depicting Joe’s “profound moment of clarity” being drowned out by a 1-800-GET-RICH infomercial perfectly encapsulates Chapter 8’s exploration of media saturation and audience passivity in mass communication. As the textbook notes, modern media environments bombard us with competing messages—often prioritizing flashy, profit-driven content (like infomercials) over meaningful reflection (p. 12). Joe’s distracted “OH, NEVER MIND…” mirrors the chapter’s warning about how hot media (McLuhan, p. 18)—low-participation, high-stimulation content—can override deeper cognitive engagement. This hit home during finals week when I absentmindedly scrolled through Instagram reels while reading about media consolidation. The textbook’s diffusion of innovation theory (p. 15) suddenly made sense: my brain, trained by algorithmic rewards, defaulted to bite-sized entertainment over complex ideas. Just like Joe, I’d chosen the “infomercial” (in my case, viral dog videos) over the “life-changing moment” (understanding how 90% of U.S. media is controlled by six conglomerates). The cartoon’s irony aligns with the chapter’s media literacy imperative (p. 22). Last month, my roommate nearly signed up for a shady “get rich quick” webinar before we researched its ties to disinformation networks. It was a real-world example of how profit-driven mass communication (p. 9) exploits distracted audiences. Yet the textbook offers hope: by recognizing these patterns—like Joe’s glazed-over epiphany—we can reclaim agency. Now, I use app timers to create “cold media” zones (p. 19) for reading, proving even small acts of resis […] “When Life-Changing Realities Compete with Infomercials” -

Nilgun Gungor (she/her) wrote a new post on the site Nilgün Güngör – Communications 1000 blog 4 hours, 46 minutes ago

Surreal Messages and Miscommunication

This comic aligns wellRead More »Surreal Messages and Miscommunication

This comic aligns wellRead More »Surreal Messages and Miscommunication -

Raffi Khatchadourian wrote a new post on the site Raffi Khatchadourian 14 hours, 35 minutes ago

NYU GSTEM student visits during the summer of 2025

Ayla Zhang will join our research group this summer through the NYU GSTEM program. NYU GSTEM is a summer program for high school juniors that […]

Ayla Zhang will join our research group this summer through the NYU GSTEM program. NYU GSTEM is a summer program for high school juniors that […] -

Castle Fong wrote a new post on the site Castle Fong Chapter Post 15 hours, 21 minutes ago

-

Castle Fong wrote a new post on the site Castle Fong Chapter Post 15 hours, 34 minutes ago

Rules are Meant to be Broken

In […] “Rules are Meant to be Broken”

In […] “Rules are Meant to be Broken” -

Castle Fong wrote a new post on the site Castle Fong Chapter Post 15 hours, 46 minutes ago

Pop Culture Not always popping

[…] “Pop Culture Not always popping”

[…] “Pop Culture Not always popping”

-

Recent Posts

-

Tsi and Kate!

03-24-2013 -

“Qualitaitive methods” course..should be prerequisite for medical students/physicians!!

03-11-2013 -

Eating habits and cancer!

03-09-2013 -

Even Epidemiologists are story teller!!

03-07-2013 -

Five dollars in pocket to Neuro-Surgeon!! Inspiring Story!!

03-07-2013

About

This template is built with validated CSS and XHTML. To download more WordPress Themes, please visit www.nattywp.com.

Open "about_text.txt" file in the theme folder to edit this text.

Recent Comments